Let’s begin with a little mathematical calculation: in the West Nile, Uganda, in the second largest refugee population of the world that, there are approximately 50 non-governmental organisations with off-grid offices. In each office, there are approximately 30 staff who require a 40KvA generator to power their offices during the day, and a 40KvA at night. Each generator consumes approximately $50,000 of fuel per year (a conservative estimate), and costs relatively the same amount to purchase each one. The math is then, as follows: $100,000 (fuel) + 100,000 (generator costs) x 50 (NGOs) = $10,000,000. Thus, in the first year of an operational refugee camp, approximately $10,000,000 is spent on energy provision alone.

Now imagine if the same investment was allocated to a mini-grid system which utilises a mix of solar and wind energy. 1 MW of wind and 1 MW of solar generation is somewhere around a $6 million investment (including O/M, land and installation costs depending on the country, and government subsidies).

Let us now lay out some ground rules to imagine how this would work:

- The government in the country where the refugee camp is located mandates that power generation in the refugee settings must be renewable.

- All NGOs in the refugee setting agree to purchase energy from the appointed provider.

- Each NGO agrees to purchase a fixed amount of KwH from the provider to ensure that the provider is able to get their return in good time, while also ensuring that a stable power supply is given.

We must also note that the average refugee camp lasts between 17-25 years.

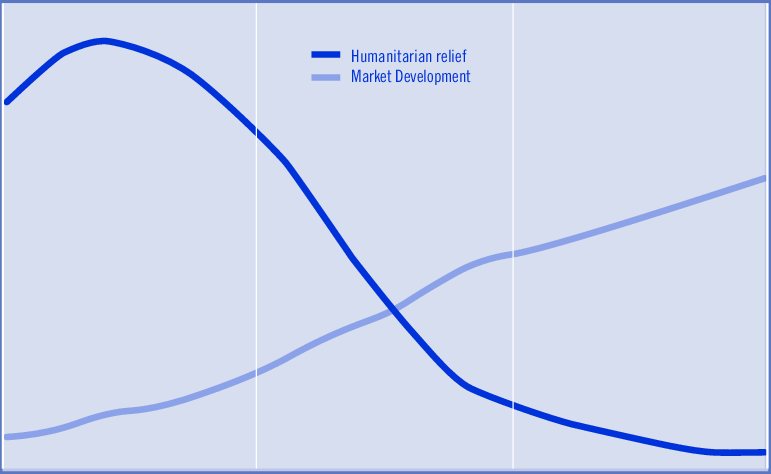

Below, we can see how profits and savings would impact the scenario:

Each NGO will save approximately $54,000 per year in fuel costs or $270,000 over five years.

Each NGO will save approximately $100,000 every five years in generator purchasing and maintenance.

At $.15 per KwH charge, 50 NGO’s will save $13,500,000 over five years.

In year one, the supplier will spend approximately $6 million to set up and operate the system.

The supplier, charging $.15 per KwH, will receive approximately $1.4 million a year in return and will make up their investment in four years. The supplier will then be profitable, barring any major issues with batteries or transmission. If this scenario remains constant for 13 more years (17 years-4 years) the profit would be around $18.2 million or 300% above the initial investment.

The agreement between the NGOs and the provider would be through a standard Power Purchase Agreement stipulating the amount of guaranteed electricity to both parties over a period of time at an agreed KwH charge. Currently diesel operates at about $.27c per Kw, therefore, anything below this amount would be a saving to the NGO. Re-doing our calculation at $.20c per KwH, the provider would be profitable in about three years.

Providers would pose an agreement with NGOs that any purchases after three years would be at a reduced rate as a benefit to being a part of the programme; this would also showcase the goodwill of the provider.

The next step would be to consider carbon: as we have just seen from the example, we are looking at displacing around 100 40KvA generators in a refugee camp. For the sake of argument, the 2×40 KvA generators per NGO use approximately 20 gallons of fuel per day, or emit around 400 lbs of carbon. If we multiply that by 50 and by 365 days in a year, we would be at around 7,300,000 lbs of carbon per year. To compensate for this, it would take around 54,000 trees over 10 years to sequester that amount, which is equivalent to over 3,800 acres of forest land to remove that carbon from the air. If we stick to our five year timeline, almost 300,000 new trees or close to 20,000 acres of forest land would be needed… or, we could just use solar and wind!

Let’s really look at what we have on the table: SDG 9.4 is clearly looking towards change in the private sector to reduce emissions and meet climate targets. But, we need to evaluate why the UN and purveyors of the SDGs have not been mobilised to their maximum potential.

By showcasing these general and simple calculations, it is clear that something can and should be done in humanitarian settings globally to change the way the UN and NGOs operate. These opportunities would also open the door to strategic and innovative public-private interactions in the humanitarian sector.

My hope is that what I write will spur conversation and get people to reflect. I encourage people to make their own calculations! And should they find that I am right, I would love to collaborate in gathering some investors and making big, long overdue changes.