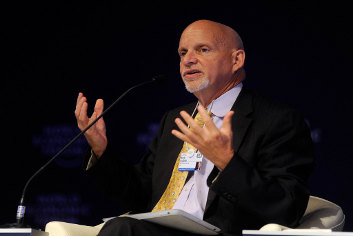

Mohamed Semra

When I was a kid, I never dreamed I could become the leader I am today because in Sudan, overpowered by the weight of society, my family bore no doctors, engineers, teachers or leaders. Along with my entire tribe of herders they conformed and accepted their place in society.My family became what society had determined them to be. My father worked 16 hours a day while my mother took care of her 7 children. I never really understood what made us different; we looked the same, believed in the same religion, yet were discriminated against for the things we didn’t possess.

As a result, I truly believed that if everyone was equal and that if material things were possessed equally among our community, we would not be divided. Instead we would be unified, replacing hate with love, and ending the prejudice placed upon myself, my family, and so many others who have been socially outcast in this way.

As a result, my mother had decided to seek a better life in a new country, one not preordained by possessions, status or wealth, where our potential will not be stifled by others preconceptions.

Australia seemed like the perfect opportunity. Once we arrived in Australia, I started my primary education and it was to my surprise the amount of love and support shown by everyday people. I played and laughed with kids of different colour and religion to me. I saw that we were all equal. I had the same education as the kid across the road even though his dad drove a BMW. If I had wanted, I could potentially lead this country. However, being a kid, I could not see beyond the veil of my dream and onto reality. We might have lived in the same area, gone to the same school, but as the years elapsed, I began to realise how different we actually were.

Faced with the various predicaments of growing up, I came to realise that I was being treated and seen differently than my peers of Australian descent. People I met for the first time seemed to have a preconceived idea of my behaviour and intentions. For instance, I would walk into a store and automatically arouse suspicion as potentially someone who would steal. I was often the subject of race jokes by many kids, such hurtful words I could not bear to repeat. This is not always the case, but the question has to be asked if this was so wrong, why did it happen in the first place?

I came to the conclusion that people choose to paint a bad picture of me due to how society has depicted people of my colour.I saw first hand that at the heart of this behaviour was a lack of understanding, which leads people to prejudge one another.

I did not let it affect me in any way, I continued to strive to become the man that society believed I could not be, and pave a way for people of my colour and become myself. However, as Carol Moseley once said, “defining myself, as opposed to being defined by others, is one of the most difficult challenges I face”.

In Sudan I was helpless to create change, in Australia I had all the tools to change the narrative. I identified the biggest problem that the African community in Melbourne is facing today, which to my understanding is a lack of role models and leaders in positions of power.

Thus, my first step on my journey to becoming a leader was applying for the leadership and debating team at my high school, both of which have never had an African member apply before. It was a daunting decision, but I needed a platform to speak on issues that matter to me. I ended up becoming both debating and school captain, but what was more rewarding, was that after two months of joining our entire debate team was now African. Furthermore, Africans in the leadership team increased from zero at the time to over a dozen. I had unknowingly started a precedent for those after me to follow, this further reiterated what I long suspected, that our community was marginalized to such an extent that few wanted to take the lead’ in changing the status quo.

Was it out of fear? No. Lack of confidence? I can personally say none of my friends lacked in that department. However, what we were deprived of was opportunity and a support system to identify and invest in our potential. It became clear that the discrimination my family faced in Sudan was the very same prejudice the individual African and refugee is battling in Australia today.

We are facing a society which regards us as aggressive, violent and uneducated, so what is our impetus to change? Why strive in a society that is built to see you fail? Why play a game you know you are going to lose every single time?

Through my experience I have come to the conclusion that in order to change the game we must first change the narrative. That is why along with my good friend Mostafa Hussein, I Co-founded Endeavour Youth Australia (EYA), a social enterprise that acknowledges the lack of cultural diversity represented within the leadership positions in Australian business, politics, government and universities.

At EYA, we are committed to making the most of the talents in our multicultural nation, beginning with our youth. We plan on giving under represented youth a platform where they can speak about the problems that matter to them most, to an audience that is in the position to best help them.

I strongly believe that given the right impetus our youth can be champions of change and the leaders of tomorrow. As a result, we are working tirelessly, both locally and internationally to identify our young leaders and invest in their futures. Through the provision of training, mentorship and opportunity anyone can achieve great things.

Mohammed Semra is UN Humanitarian Affairs Peace Ambassador