Transformative justice is a general philosophical strategy for responding to conflicts. It takes the principles and practices of restorative justice beyond the criminal justice system. It applies to areas such as environmental law, corporate law, labor-management relations, consumer bankruptcy and debt, and family law. Transformative justice uses a systems approach, seeking to see problems, as not only the beginning of the crime but also the causes of crime, and tries to treat an offense as a transformative relational and educational opportunity for victims, offenders and all other members of the affected community. In theory, a transformative justice model can apply even between peoples with no prior contact. In contrast to restorative justice, no quantification or assessment of loss or harms or any assignment of the role of victim is made, and no attempt to compare the past (historical) and future (normative or predicted) conditions is made either. The victim is not normally part of the transformative process, but can choose to be. Participants agree only on what constitutes effective harms reduction, which may include separating or isolating perpetrator and victim. As in transformative learning, one works from desired future states back to the present steps required to reach them. The issue is not whether the perpetrator may make a choice to do something similar again, but whether the community is willing to support the victim and perpetrator in some form of contact. This model may have roots in the work of Samuel Tuke and B. F. Skinner but departs by relying on individual volunteers’ caring and supporting capacity, not any socially imposed etiquette derived from civilization. Transformative justice theory has been advanced by Ruth Morris and Giselle Dias of the Canadian Quakers. Philly Stands UP Art as a vehicle to justice part 2

Related Articles

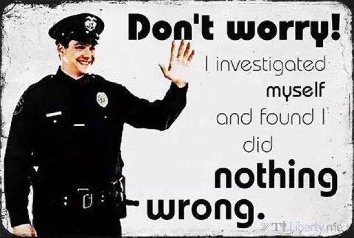

Who is watching the ones who watch?

observing police abuse

ICTJ and the effort to redress legacies of massive human rights abuse

The price to pay for exposing the Mafia

how Roberto Saviano's life became a living hell

what is the number one cause of death for young Americans?

The judge against the world's worst criminals

The position of Fatou Bensouda

Is it possible to decrease sexual violence?

justice for survivors

Discuss your conflicts, overcome your racism

the efforts of Krzysztof Czyzewski

The triumph of the rule of law

the World Justice Project

The Brazilian women as targets

and the project of a lawyer

Waiting 30 years for his execution date

Santiago Esteinou's documentary The Years of Fierro

![]()

STAY IN TOUCH

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

AND RECEIVE OUR LATEST STORIES