On May 2011, demonstrations occurred across Spain organized entirely over the internet in protest against the economic crisis. The arrest of 24 demonstrators at the end of the march in Madrid led to a spontaneous sit-down in Madrid’s main square, the Plaza del Sol. Facebook, twitter and other social media called for a mass sit-down that same evening which then became a more permanent camp. This was the start of the los indignados movement although it had roots in other movements such as VdeVivienda which began in 2006 in support of the right to affordable housing, Precarios en movimiento, a loose network of groups struggling against the lack of certainty (precariedad) in employment, housing, pensions, health and education and Juventud Sin Futuro (Youth without a Future) which coalesced in Madrid’s universities in April 2011 around the slogan ‘no house, no job, no pension, no fear’. Opinion polls suggested broad social support for the movement because it reflects the concerns of ordinary people. A poll conducted for the BBC World Service on economic fairness, showed that while in 2009 66% in Spain felt that economic benefits and burdens had not been fairly shared, by 2012 this figure had increased dramatically to 92% (Globescan, 2012). Over the last years, the indignados do have some concrete achievements to their name. Their support for the anti-eviction platform (PAH), which seeks to prevent authorities and banks from leaving families unable to pay their mortgages out on the street, is probably the most notable example. The eviction of around 200 families from their homes each day in 2011 under Spain’s strict mortgage laws is one of the most brutal indicators of the country’s current crisis and a direct legacy of the burst real estate bubble. The involvement of activists in this cause has stopped only a fraction of the slated evictions. But it has drawn attention to an anomaly in Spanish law that leaves many families owing tens or even hundreds of thousands of euros after they have had their homes repossessed. Another development has been the establishment of neighborhood assemblies, in which people voice concerns about local issues. Some of these are little more than ways for the verbose to let off steam, but in other cases, barrio “service exchanges” have been set up, whereby an electrician, for example, will fix the lighting of a neighbor, who will fix a computer by way of payment. These assemblies clearly are not an adequate replacement for the formal institutions of democracy, but they do serve another, albeit abstract purpose: they have got many ordinary Spaniards, who until recently had seemed resigned to the complacency, corruption and lack of accountability of their leaders, engaged in politics and thinking about why the economy is in the mess it is.

Related Articles

transformation and the NoVo Foundation

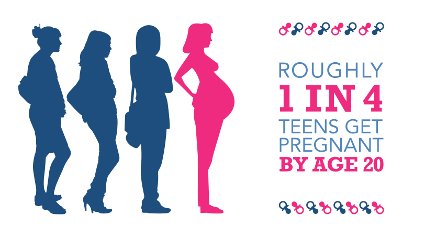

how to prevent teen pregnancy

flying is all but impossible for disabled people

Christian Bason and the MindLab in Denmark

what happened when an optometrist met a political activist

insights from the Food Ethics Council

and the benefits of a supplement

The power of music to change lives

the Sound Foundation, an excellent initiative from UK to Uganda

Would you give away half your house?

the story of a family who did

Know your environment: the Bullfrog Films

a major resource for documentary films

![]()

STAY IN TOUCH

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

AND RECEIVE OUR LATEST STORIES