In the past couple of months I had some time to reflect on ten years of working with civil society organizations for humanitarian aid and development cooperation, while getting up to speed with my role at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs focusing on aid effectiveness.

During my time working with civil society I have used Pestoff’s triangle to conceptualize civil society space. It consists of three boundaries that separate the public and private domains, the for-profit and not-for-profit domains and the formal and informal domains. I came across this model in a partnership policy document of ICCO while preparing for a grant application back in 2010. It has since been a handy tool in furthering the dialogue around good governance, sustainable entrepreneurship and responsible citizenship.

I discovered that others have also used it to identify spaces where public-private partnerships may emerge and to argue why civil society should be part of the equation (like Avelino & Wittmayer, 2014). However, during the last two years working with Tearfund, a faith-based NGO (FBO), I failed to demonstrate the relevance of the model to the overall theory of change of Tearfund and help them increase their engagement with institutional actors like market players and government agencies.

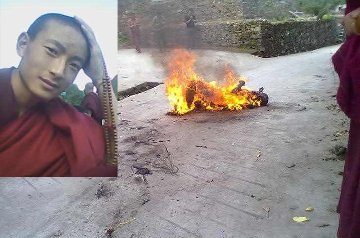

Models like the one of Pestoff, find their origin in welfare state development policy and practice, with the state responsible for wealth redistribution. It insufficiently pays attention to indigenous institutions and/or faith systems which also deeply influence people’s behavior and how they act as citizen, NGO-worker, entrepreneur or civil servant. Public agencies and secular NGOs increasingly realize that the domain of faith contains transformative power and is worth exploring.

It is very much part of reality for a majority of people in developing countries (see contributions by Brenda Bartelink). It helps people to have a purpose-driven life, provides comfort and hope in situations of despair and may provide guidance when dealing with the challenges of life. Tacit knowledge, derived from these faith systems or oral traditions, may at times outweigh academic arguments in their ability to support or obstruct change.

Observations are expanded from the known physical world into the unknown spiritual world with both worlds carrying truth claims influencing people’s hopes and fears and giving them a sense of purpose. Apart from religion, other rituals and cultural traditions may also harbor a wealth of knowledge that enables people to live in peace with themselves, their neighbours and their surroundings.

Adding science and conscience domains

To accommodate both tacit knowledge as well as academic knowledge, a knowledge dimension could be added to Pestoff’s model. By separating this dimension in academic and tacit knowledge, it adds two domains to the model: the domain of science and the domain of conscience, with a hybrid space in between. The conscience domain has been developed over centuries of human experience and transfers from one generation to the next and stretches out from the known into the unknown. It is enshrined in holy texts and has been codified in declarations like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Faith in whatever form or shape extends the furthest into this unknown territory, claiming a kind of knowledge that is based on a revelation of divine promises and rather validated by human experience than by scientific proof. Also the science domain has a long history, with contemporary science dating back to the days of Plato. And even long before that highly sophisticated scientific thinking was found in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Orient and with the Maya civilization to mention a few.

What is the value add?

Inclusion of the knowledge dimension turns the Pestoff model into a 3D model adding a fourth hybrid boundary between academic and tacit knowledge. The hypothesis is that the overlap between the two kinds of knowledge provides for civil society space. Apart from being confined between state, private sector and the family domain, civil society is the space where both people’s value systems as well as academic research contribute to a global conscience that leads to negotiated goal setting.

In this space academic knowledge has a role in validating some of the knowledge derived from tacit knowledge while also exposing flaws in thinking. Likewise tacit knowledge may put necessary restrain on scientific advancement, where research objectives have no societal contribution or where research methods are considered unethical.

Hence, inclusion of the knowledge dimension may help us understand why civil society space is diminishing beyond state interference with private sector operations or infringements with the informal private space of families and communities. It also creates an obligation for science to help validate some of the tacit knowledge that may be part of endogenous knowledge systems or faith systems, so that it can be operationalised in the public domain and contribute to the preservation of public goods and ensure human rights are respected.

Islands of predictability

The Sustainable Development Goals were born in this space and serve as reference points for our global conscience. Governments and companies aiming for short-term profits in particular will be quick to question the realism of these promises and would prefer others to deliver on them first. In her best seller The Human Condition, philosopher Hannah Arendt already stated that international treaties serve as “islands of predictability in oceans of insecurity” (Hannah Arendt, 1957). In order for the SDGs to be delivered on, civic space needs to be maintained and increased as much as possible aiming for convergence of objectives from the other domains towards sustainable development.

Can we measure changes in civic space?

Mathematically it remains virtually impossible to calculate the size of civic space, which has been a challenge as long as the concept exists. Boundaries of civil society remain blurred on each of the dimensions with a lot of hybrid space surrounding it. Hence the model still won’t resolve the challenge of measuring civil society space. Nevertheless I hope this adapted version of the Pestoff triangle helps in furthering the thinking on aid effectiveness, paying due attention to the contributions of both academia and indigenous knowledge and/or faith systems and actors while developing common goals that will help shape a purpose driven international development practice

REINIER VAN HOFFEN is Senior Advisor at the International Cooperation Office