The Rwandan Civil War began in October 1990 when the Tutsi Rwandan Patriotic Front invaded Rwanda from Uganda in an effort to unseat the government of President Habyarimana. Government-controlled forces attacked minority Tutsi populations and moderate Hutus. In turn, the RPF attacked numerous Hutu civilian targets and reportedly recruited child soldiers. A ceasefire agreement was reached in 1992, and the war officially ended on 1993. Despite the accords and the agreement on power-sharing, however, tensions persisted between Hutu and Tutsi factions. In the spring of 1994, President Habyarimana was assassinated, which sparked the genocide that took place over 100 days killing an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 people. Due to the intervening violence, the National Unity and Reconciliation Commission was not set up until 1999, when it was established by the new Transitional National Assembly. At that time, the Commission was at last empowered to organize national public debates aimed at promoting reconciliation, foster tolerance and denounce any ideas aimed at disunity. It was tasked to educate Rwandese on their rights and the rights of others, draft laws to foster reconciliation. The findings of the commission’s reports on national summits and reconciliation activities have revealed that political and socio-economic issues are more responsible for divisions that any fundamental differences between Hutus and Tutsis. Aloisea Inyumba, former commissioner and executive secretary of Rwanda’s Unity and Reconciliation Commission, declared : “Rwandans are now discovering, to their surprise, that the ethnic differences which have been so much magnified in the past are not the real differences. The issue in Rwanda was bad governance, the culture of impunity and social injustices by successive ruling cliques. These have affected almost every Rwandan in one way or another”. At the same time, few people would deny the rather stunning progress in Rwanda over the past 15 years. First of all, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was the first international tribunal in history to deliver verdicts against persons responsible for committing genocide. The ICTR was also the first institution to recognize rape as a means of perpetrating genocide. With 61% of the population being under the age of 24, the Rwandan government has made education a top priority, has spended 17% of it’s budget on education and has made primary and secondary school compulsory for both boys and girls. Women hold 64% of seats in Rwanda’s parliament, which is more than any other country in the world. The female majority has ensured that laws aimed at raising the status of women are at the forefront of political discourse. 90.6% of the population is enrolled in Rwanda’s national health program. Due to greater access to health services there has been a decline in death from diseases like malaria, which saw an 85.3% drop between 2005 and 2011. Rwanda has also made significant progress in restoring the economy to pre-1994 levels with an average annual GDP growth rate of 7%-8% since 2003. The successful implementation of the Community Courts, which have dealt with over 1.5 million cases of genocide crimes and the enactment of laws to prevent the spread of genocide ideology, are among many important steps taken to bring about justice and reconciliation, and ensure that Rwanda remains stable and safe. The media in Rwanda, like many other sectors, is young but growing and enjoying relative liberty. Rwanda’s progress is finally clear in social development, the civil service and the fight against corruption. All of this, in a country who has recently experienced the worst genocide of the last 60 years. Reconciliation village Talking to your family’s killer

Related Articles

how do you overcome religious divisions?

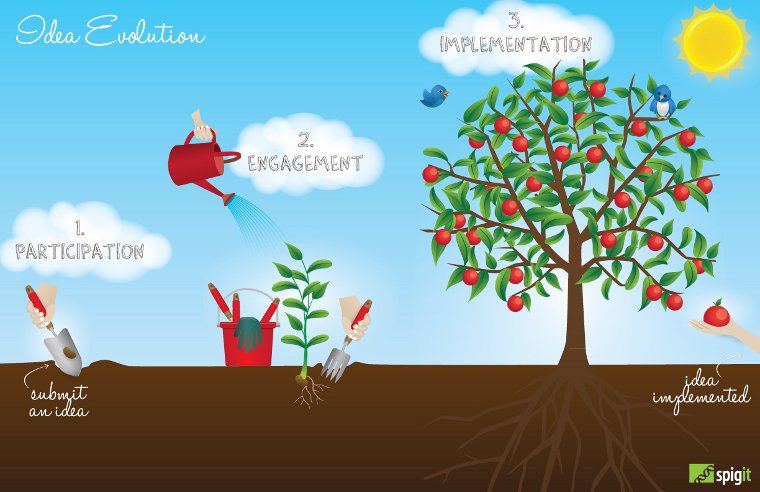

A small city can also innovate

the story of Manor Labs

The world required by the young

watch the documentary of P. Davidson

Unlocking the potential of innovation for development

In her article to OLBIOS, Paola Cervo shows how international aid could play a significant role in supporting innovation for social good in developing countries

and it's political prisoner number one

the work of the actor with UNICEF

We are experiencing more peace, according to the Global Peace Index But the reality around the globe tells a different story, one that makes peacebuilding necessary, writes Vahe Mirikian, OLBIOS Correspondent in USA.

creative programs for palestinian children

what happened to the American sense of community?

the work of Imam Aziz

![]()

STAY IN TOUCH

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

AND RECEIVE OUR LATEST STORIES